Ottawa — Infectious disease experts say Canada’s loss of measles elimination status underscores the urgent need for renewed investment in public health, stronger vaccine confidence, and solutions to the ongoing primary care crisis.

On Monday, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) officially revoked Canada’s measles-free designation, which the country had held since 1998. The move follows a prolonged outbreak of the virus across several provinces that has persisted for more than a year, with more than 5,000 cases reported nationwide.

According to experts, the setback reflects years of underfunding in public health, inconsistent vaccine tracking, and widespread misinformation about immunization. Dr. Dawn Bowdish, an immunologist at McMaster University, said a lack of resources has left health workers unable to effectively reach vulnerable communities or respond swiftly to outbreaks. “Public health workers don’t have the resources they need to do enough vaccination outreach and boost surveillance,” Bowdish said.

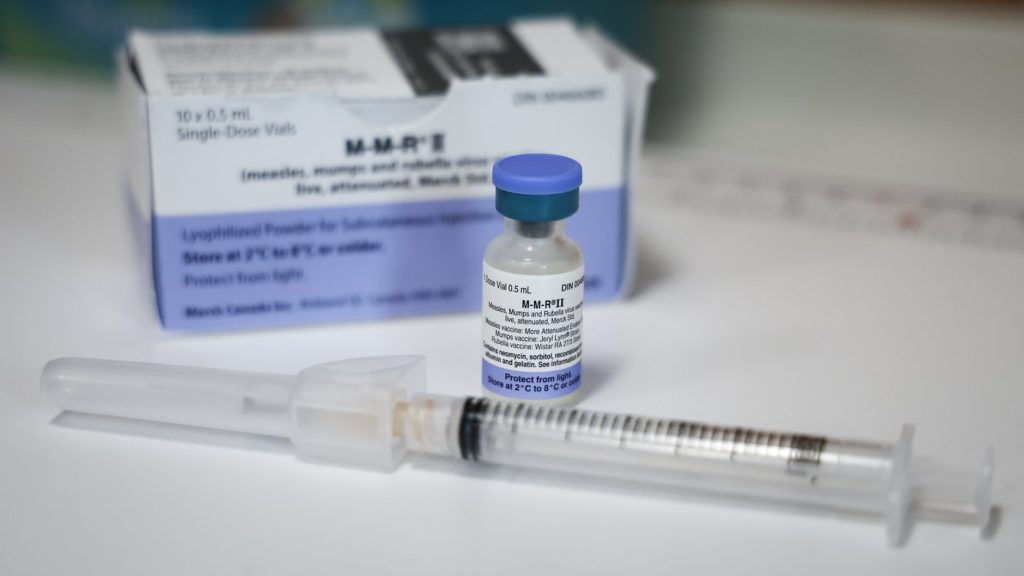

She added that the absence of a national vaccine registry makes it difficult for Canadians to verify their immunization history, especially for those who received vaccinations in other provinces or countries. “If families don’t have a primary care doctor or nurse practitioner, their kids are at risk of missing vaccinations,” Bowdish noted, pointing out that pharmacies generally cannot administer the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine to very young children.

Experts emphasize that to regain measles elimination status, Canada will need to interrupt all transmission of the current strain for at least 12 consecutive months, while also demonstrating improvements in surveillance and rapid response capacity.

Bowdish also called for stricter enforcement of school vaccination policies, noting that overly permissive exemption rules in provinces like Alberta and Ontario have contributed to declining immunization rates. “We’re way too liberal with our exemption rules,” she said. “That has contributed to falling vaccine rates.”

PAHO officials say that regaining elimination status will require Canada to complete its national electronic vaccination record system, which currently covers only five provinces and one territory. Dr. Daniel Salas, executive manager of PAHO’s Special Program for Comprehensive Immunization, said a unified record-keeping system is crucial to monitor vaccine coverage and identify gaps.

Dr. Monika Naus, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Population and Public Health, added that public health agencies must identify whether low-vaccination communities are underreported due to missing records or genuine vaccine refusal. “That really is something that the public health community should be able to get a handle on,” she said.

Both PAHO and Canadian experts stress the importance of building trust within close-knit unvaccinated communities, noting that cultural understanding and tailored outreach are essential to improving vaccination rates. “It’s probably false to consider that people who are resistant to vaccination will never be vaccinated,” Naus said. “Even in communities with low uptake rates, there are probably improvements that can be made.”

Bowdish concluded that the path forward will demand significant funding and political will. “There’s no two ways about this,” she said. “This will take money — a lot of money — and it will take a lot of investment.”